What is the POY Latam?

POY Latam was created in 2011 by Pablo Corral Vega and Loup Langton to celebrate excellence in documentary photography in Latin America. Over the years, it has established itself as the most important non-profit competition in the region, with a unique feature: a public, open, and transparent judging process that turns each edition into a living school of photography.

More than an award, POY Latam is a space for meeting and learning. Through competitions, exhibitions, workshops, and publications, it promotes the talent of thousands of photographers and visual creators, defending human dignity, memory, and the diversity of our societies.

On this page, you will find the gallery of POY Latam 2025 winners, a visual testimony to the strength, creativity, and commitment of those who tell the stories that define our region.

POY Latam is the most important documentary photography contest in Latin America.

celebrates excellence in photography and connects visual creators in the region. We are proud to promote a platform that highlights the stories that define and enrich our diverse and kaleidoscopic identity.

The numbers

In its 2025 edition, POY Latam received 20.732 images submitted by more than 1.155 visual creators from all Ibero-American countries. The public deliberations, broadcast live, were followed by tens of thousands of people through our streaming platforms, confirming that POY Latam is not just a contest, but a space for collective learning and a true community around documentary photography.

20.732

IMages

+1155

PHOTOGRAPHERS

The next edition of POY Latam will be in 2027.

POY Latam is a biannual competition that, since its creation in 2011, has been held in different cities and countries in Latin America, becoming a benchmark for documentary photography in the region.

Since 2021, the competition has been held in a virtual format, allowing judges and technicians from multiple countries to come together and share their deliberations with an increasingly wider audience. The 2025 edition attracted tens of thousands of followers around the world, confirming POY Latam as an open school, a meeting place, and a vibrant community centered around the image.

Our main contest

Pictures of the Year International (POY), was created in 1944 by the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Journalism. Its photojournalism program is the oldest in the world and one of the most respected.

Transparent judgment

The POY Latam judging process is broadcast live, making it one of the few competitions in the world with a policy of total transparency and openness. All decisions are made in a reasoned manner and under the watchful eye of the community.

Advisory Council

The most important decisions are made as a collegiate body. The council is constituted by Gael Almeida, Angela Berlinde, Maíra Gamarra, Manuel Ortiz, Yinna Higuera, Gisela Volá, and Tiago Santana

The current director

The current director is Pablo Corral Vega, Ecuadorian photojournalist, lawyer, writer, artist, and cultural manager who has published his work in National Geographic magazine and other international publications. He is the author of eight books.

How much does it cost to participate?

It is completely free for photographers thanks to the generous contributions of several sponsors. POY Latam is a non-profit project.

Mission and Vision

Connecting visual creators in Ibero-America and building communities through art and documentary photography. Promoting a deep understanding of the essential issues facing humanity, always respecting human dignity and reflecting the richness and complexity of our histories.

To make POY Latam the most influential platform for documentary photography in Latin America, an open and educational space that projects the voices of the region to the world, strengthening democracy, cultural diversity, and collective memory through the power of images.

The New York Times

This enthusiasm reveals much about the rapidly changing world of photojournalism in Latin America. When Mr. Corral and Mr. Langton met 20 years ago, a photojournalist in Quito, Ecuador, often didn’t even know other photojournalists in neighboring cities. Photographers in Latin American countries worked mostly alone, often learning about their own countries from European and United States-born photographers whose images graced the covers of glossy international magazines.

Julie Turkewitz

© Kita Wichhu “Posthumans and cyborg dreams of + beings in the Andes” is a visual essay that began in 2023 in the department of La Paz, Bolivia, based in its highland villages and the city of El Alto.

Al Jazeera

Latin American photography is too broad to be defined in general terms. However, there are some common trends throughout the region. Pablo Corral Vega, Ecuadorian co-founder of POY Latam, believes that contemporary photojournalism in the region is breaking with traditional ways of seeing. One trend is the blurring of the usual separation between art and journalism. Documentary photography highlights the urgent problems affecting society, but a young generation is reinventing the way images tell the story of the world and what photojournalism consists of. Moving freely between journalism and aesthetic photography, they blur the conventional boundaries between art and news.

Manuela Picq

The Winners of 2025

CLASSIC FORMAT

The classic categories of POY Latam are at the heart of the contest: documentary photojournalism, without digital manipulation, which seeks to honestly portray the major events of our time and the daily life of our communities. Here, we recognize the power of a tradition that remains fundamental: telling the truth through direct images that inform, move, and endure as collective memory.

These categories recognize both individual photographs and photo essays, evaluating narrative coherence, rigorous editing, and each author’s ability to offer a unique perspective. From protests and humanitarian crises to the intimate gestures of everyday life, the finalists in this edition reminded us that photojournalism is more than just a record: it is a way of understanding the world and maintaining an ethical commitment to the dignity of the people portrayed.

In reviewing these series, the judges emphasized essential concepts: the importance of patience and closeness in narrating everyday life, the need to transform the urgency of the news into visual memory, the power of portraiture to reveal identities and absences, and the responsibility of Ibero-American photographers to focus their gaze both on the region and on major international conflicts. The classic categories of POY Latam thus reaffirm the profound meaning of photojournalism: to bear witness, raise questions, and defend the truth in times of uncertainty.

POY Latam would not be possible without the generous and committed work of those who make it happen. I would like to express my deepest gratitude to the judges for this edition, who devoted countless hours to viewing, discussing, and reflecting on thousands of images with rigor, sensitivity, and respect. I would also like to thank the moderators and technical team, whose work was marathon-like and precise, ensuring that each deliberation reached the entire community with transparency. My gratitude also extends to the Advisory Council, a group of colleagues and friends who accompany every strategic decision made by POY Latam and ensure that this project is built as a collegial, open, and pluralistic body. And, of course, to the photographers and visual creators of Ibero-America who entrusted their work to this space: you are the heart of POY Latam.

The 2025 judging was, as always, a shared learning experience. Over several days, we listened to the judges debate what it means to narrate everyday life, record the news, portray people, redefine memory, and experiment with new visual languages. There were disagreements and consensus, doubts and certainties, but above all there was a clear conviction: photography continues to be an essential tool for understanding ourselves as societies. Each category became a window through which to see ourselves from within and also to recognize ourselves in the gaze that our photographers project onto the world.

Why is POY Latam important, and why should we continue with it? Because this contest is not just an award ceremony: it is an educational process, open and transparent, that strengthens our visual community. Because it offers a space for recognition and collective learning, where the judges’ experience and public deliberations become a learning experience for everyone. And because, at a time when democracy, human rights, and the environment face growing threats, we need more than ever honest, critical, and profound images that remind us of what is at stake.

POY Latam 2025 confirmed once again that Ibero-American photography is in full swing: diverse, bold, committed. That vitality drives us forward. Continuing with POY Latam is, at its core, an act of faith in the power of images to build memory, defend human dignity, and pave the way toward a more just future.

Pablo Corral Vega

Photographer of the Year

The debate surrounding the Photojournalist of the Year category revolved around one central idea: the need for a portfolio to be more than just a collection of striking images, but rather the expression of a consistent, rigorous, and committed perspective. For the judges, this recognition requires versatility—the ability to move between news, everyday life, social conflicts, and long-form essays—but also consistency, a visual voice capable of sustaining itself across different registers without losing narrative force.

Throughout the deliberations, essential questions arose: What makes a story relevant to an entire community? How can the urgency of the news event be balanced with the depth of the documentary perspective? To what extent can the photographer go beyond the moment to construct a narrative that provides context and understanding? In this space, the jurors insisted that editing is as decisive an act of authorship as pressing the shutter button: the way a portfolio is constructed reveals the clarity—or fragility—of the journalistic vision.

The essays reviewed showed the diversity of concerns affecting our region and the world: from violence against the press in contexts of repression to the intimacy of families struggling to maintain a home amid the housing crisis; from the harshness of exile and migration to the persistence of daily life under military occupation regimes. Each project sparked a debate about the scope of photojournalism: some stood out for their courage and access in high-risk situations; others for their sensitivity in narrating the intimate and the vulnerable; and still others for their ambition to place local processes in a global context.

In the end, what the judges valued most was the ability of certain portfolios to combine the power of denunciation with the sensitivity of human testimony, constructing images that not only inform, but also invite understanding and dialogue. It was this ability to maintain a broad and committed perspective, to open up questions rather than close off answers, that defined the Photojournalist of the Year.

Daily Life (Single)

In the Everyday Life category, the judges emphasized that a good photograph not only captures a moment, but also illuminates who we are and the challenges we face on a daily basis. The discussion revolved around the ability of a single image to convey complexity: the intimate and the public, the beauty and harshness of everyday life, that which defines the experience of living in Ibero-America.

The finalist images offered different perspectives on this quest. From the scene of a man on a night bus in Guatemala, where red light illuminates routine and shared fatigue, to the serene strength of a shepherd guiding his llamas in the Argentine puna. There were also photographs that confronted fragility and hope, such as that of a Brazilian mother breastfeeding her son with “brittle bones,” surrounded by her daughters: an intimate portrait of resilience, love, and state neglect.

The jury emphasized that everyday life is not always found in grand gestures, but rather in the persistence of humanity. The photos that stood out managed to combine powerful composition with a deep sense of cultural belonging. The winning image—a mother with her children on the outskirts of Cuiabá—was recognized as a painful yet luminous synthesis of our reality: life that insists on flourishing even in adverse conditions. Other scenes, such as children playing in the shadows on a court in Santiago or the intimacy shared on a bus ride, were celebrated as honorable mentions, reminding us that everyday life can also be revealing and transcendent.

Daily Life (Essay)

In this category, the judges emphasized that a good essay on everyday life must achieve the most difficult thing: to show the intimate and the common with depth, to reveal what sustains daily life without resorting to sensationalism. The discussion focused on how to narrate everyday life without falling into repetition, how to find in the simple—the gesture, the space, the light—the density of a culture or a community. One essential idea was repeated: photographing everyday life is, at the same time, an act of proximity and patience.

The finalist projects offered a diverse mosaic of approaches. In Brazil, the Calunga Empire festival revealed the strength of Afro-descendant traditions in a vibrant essay, with an intentional use of light and color that conveyed both the ceremonial and the intimate. In Galicia, the focus was on elderly people who remain in depopulated villages: images of great delicacy, capable of transforming loneliness into a poetic testimony of dignity and abandonment. In Oaxaca, cantinas became the setting for exploring male vulnerability, a space where the harshness of machismo dissolves for a moment in shared confessions and silences. And in Xingu, Brazil, a work portrayed ancestral ceremonies that reaffirm the identity and memory of an indigenous people, although the judges debated whether the gaze should go beyond the ritual to approach daily life in all its breadth.

The final consensus particularly valued authenticity and intimacy. The winning essay, focused on the celebration of the Calunga Empire, was recognized for conveying the energy of a community from within, with images that combine movement, portraiture, and composition in a modern and honest narrative. Other works—the intimate portrait of old age in Galicia, the emotions contained in the cantinas of Oaxaca, and the spirituality of the Xingu—were distinguished as honorable mentions. For the judges, all of them reminded us that everyday life is not trivial: it is the essential stuff of our identity, the terrain where memory, resistance, and hope are played out.

News (Single)

In the individual News category, the judges noted that a news image cannot rely solely on the power of the event. The impact of the moment is important, but it must be accompanied by a clear narrative, precise composition, and a caption that provides context and ethical responsibility toward the people portrayed. The debate revolved around the fundamental question of how to transform the urgency of the news into a visual document that transcends the moment and remains in the collective memory.

The finalist photographs showed the intensity of Latin American unrest in recent years: the repression of retirees in Buenos Aires, the humiliation of a young man in Quito forced to drop his pants in front of soldiers, the pain in Guayaquil after the murder of teenagers by state forces, and the protests in Caracas against Maduro’s reelection. There were also images of contexts less visible in the headlines, such as the health crisis of the Yanomami in Brazil, where entire communities were devastated by illegal mining and lack of medical care. These photographs reminded us that the news is not always limited to the public square: it can also be found in the jungle, in a house devastated by a hurricane, in the gloom of a funeral.

The winning image—the wake of a teenager in Guayaquil, accompanied by his teammates—was recognized for its impeccable composition and the emotional depth with which it conveys the tragedy of state violence. Other notable images, such as the air evacuation of a sick Yanomami man, the indigenous woman with white tears of milk of magnesia during a protest in São Paulo, or the fire that destroyed homes in Valparaíso, broadened the scope of what we understand as “news.” For the judges, this category reaffirmed that photojournalism does not just record events: it helps us understand their human and political significance.

News (Essay)

In the News Essay category, the judges emphasized that telling a news story through a series requires more than gathering striking images: it is about building a coherent visual narrative, one capable of sustaining tension, variety, and rhythm. A good essay is not an archive of records, but a perspective that organizes and gives meaning to the experience of the event. The debate revolved around which essays managed to transcend the moment and offer a story with a beginning, development, and closure, and which remained a succession of scenes without a connecting thread.

The finalist projects addressed some of the most urgent crises in our region. From the devastating floods in southern Brazil and the fire that destroyed communities in Mexico, to political repression in Venezuela and migration processes across the Darién and Panama. Another notable work portrayed the arrival of satellite technology to Amazonian communities through Starlink, opening a discussion on how new forms of connectivity are reshaping social and cultural life in isolated territories.

The winning essay—focused on the catastrophe in Valencia, Spain, where entire neighborhoods were buried in mud after torrential rains—was recognized for its narrative strength and its ability to photograph not only material devastation but also the dignity and desolation of survivors. The judges valued the project’s range of perspectives, from the chaotic violence of the streets to the silent intimacy of a ravaged home. Other essays were distinguished as notable: the prison crisis in El Salvador, the elections in Venezuela, interrupted migration in Panama, the breakthrough of satellite connectivity in Amazonian communities, and the fires in Mexico. For the judges, this category was a reminder that the photo essay is an essential tool of journalism: it allows us to grasp the human scale of the news and to connect scattered events into a narrative with memory.

Democracy & Human Rights

This category placed a decisive question at the center: How can photography document attacks and threats to democracy while at the same time defending the dignity of those who suffer their consequences? The judges stressed that a good essay in this field is not limited to recording acts of repression or protest: it must also build memory, open spaces for reflection, and become a testimony that, in the future, allows us to understand what happened in our region.

The finalist projects offered a disturbing map of Ibero-America: the attempted coup in Brasília and violence against journalists; the Venezuelan opposition’s struggle against an authoritarian system; the mass arrests in El Salvador under the state of emergency; the lethal repression of protests in Peru; and the persistence of memory in Argentina, where trials for dictatorship-era crimes are still ongoing. There were also perspectives on migration processes in Mexico and Central America, which revealed not only the violence of the journey but also the intimate anguish of those forced to flee.

The winning essay—focused on the electoral process in Venezuela, from opposition primaries to persecution and exile—was praised for its narrative strength and for the way it turned a political crisis into a human story. The judges highlighted the relevance of the subject and the quality of the editing, capable of articulating a clear and powerful story. Other works were recognized as notable: the images of Brasília, with their calm look at political violence; the documentation of the state of emergency in El Salvador; the denunciation of repression in Peru; migration in Mexico amid more restrictive policies; and the memory trials in Argentina. All reminded us that the defense of human rights does not take place only in courts or parliaments, but also in the images that preserve the memory of what must not be repeated.

Portrait

Portraiture is perhaps the most direct and most difficult genre: to look someone in the eyes and allow that gaze to reveal more than just a face. In this category, the judges emphasized that a good portrait must transcend the surface; it must carry history, dignity, and context. A portrait is not just about technique: it is also a relationship of trust and respect, a silent pact between the one who looks and the one who is looked at.

The finalist projects showed the enormous diversity of approaches in Ibero-America. From the harrowing intimacy of Indigenous communities in Colombia facing a wave of youth suicides, to the delicate transmission of ancestral knowledge in Cusco, where father and son preserve together the tradition of rebuilding an Inca bridge. There were also works exploring the pain of women who survived breast cancer, portrayed with the rawness of wet collodion, or the silent testimony of relatives holding the clothes of their loved ones killed during protests in Peru. And alongside those pain-laden gazes, a luminous essay on escaramuzas in Mexico celebrated the strength and grace of women riders reclaiming their place in a historically male space.

The winning essay—focused on the suicide crisis in the Embera community of Chocó, Colombia—was recognized for the depth and courage of its approach. The judges highlighted how these portraits, intimate and respectful, succeed in making a silenced tragedy visible, preserving the dignity of those portrayed while at the same time pointing to the urgency of the issue. Other projects were recognized as notable: the escaramuzas in Mexico, the generational handover in Cusco, the Survivors series of women with breast cancer, and the absent portrait of mourning clothes in Peru. All served as a reminder that, ultimately, portraiture does not merely show a face: it confronts us with memory, with resistance, and with the human capacity to reveal truth in a still gesture.

Sports

Sport, at its core, is not just competition: it is also ritual, catharsis, identity, and memory. In this category, the judges insisted that a good sports essay must go beyond recording victory or defeat to show how sport permeates cultures, families, and communities. What was valued was the photographers’ ability to discover in athletic practice a mirror of our societies: spaces of resistance, celebration, and belonging.

The finalist works offered a broad journey: from the intimacy of a family of horse riders in the high Peruvian altiplano, living between tradition, risk, and mourning; to the collective euphoria of Botafogo fans in Rio de Janeiro, who turned a stadium into a temple during the Libertadores final. There were also stories of discipline and dreams, such as that of a Bolivian teenager fighting to make her way in women’s boxing, and narratives about Indigenous peoples who, through intercultural olympics, defend their land and culture in the name of sport.

The winning essay—centered on the extreme wrestling of Zone 23, on the outskirts of Mexico City—was celebrated for its narrative power and visual complexity. The judges highlighted the way the series weaves together action, portraiture, and context, conveying the violence, energy, and cathartic intensity of a spectacle that is, at once, sport and social release. Impeccable editing, the consistent use of flash, and the ability to portray both fighters and spectators turned this work into a unique document. Among the notable essays were the equestrian memory of the Parizoto family in Peru, the overflowing passion of Botafogo fans, and the ancestral discipline of Indigenous peoples in their traditional games. All served as a reminder that sport is not only played: it is also lived, inherited, and transformed into a collective story.

Photojournalists in the World

Just a decade ago, few Ibero-American photographers managed to work on the world’s major stages. Today that reality has changed: more and more photographers from the region are standing shoulder to shoulder with the best in the world, bringing their singular vision to global conflicts and transformations. This category celebrates precisely that ability of our photographers to tell stories beyond our borders, with a sensitivity that combines the rigor of international photojournalism with the cultural depth of Ibero-America.

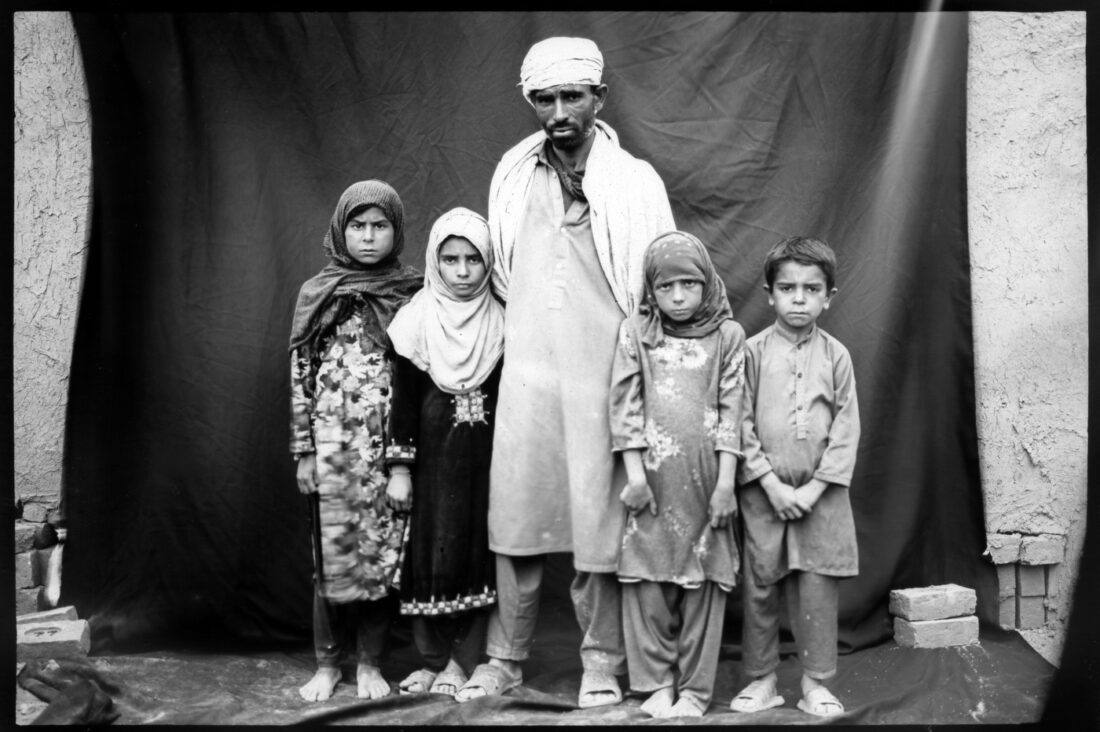

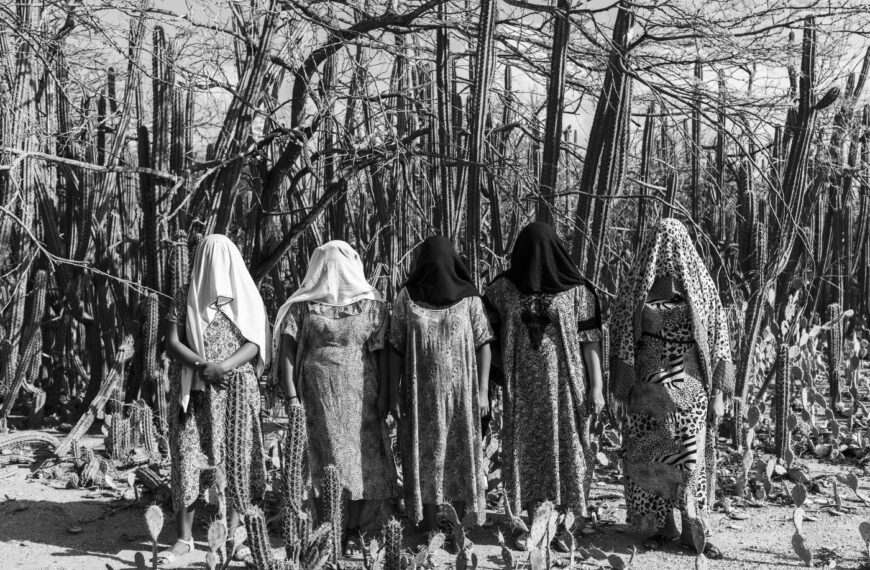

The finalist projects presented a map of crises and challenges that define our time: the migration tragedy in the Mediterranean, where the rescued embody both hope and displacement; the violence in Lebanon, marked by bombings and the presence of militias; the forgotten war in the West Bank and the ongoing devastation in Ukraine; and a return to Afghanistan to portray, through a unique photographic process, life under a new regime. There were also perspectives on global events from more intimate angles, such as the Vatican awaiting a new Pope. In all cases, the judges valued the quality of the editing and, above all, the ability to transform well-known events into narratives that reveal something new—whether through privileged access, the poetic construction of images, or the humanity with which the protagonists were portrayed.

The winning essay—focused on Afghanistan—was recognized for its aesthetic and conceptual strength, but also for the courage of revisiting a territory photographed to exhaustion and finding a different gaze. Created with wet collodion, the project blends artisanal technique with contemporary urgency and offers a distinct portrait of a country scarred by war. Other series were highlighted for their narrative power: the exodus from Libya to Europe, the violence in Lebanon, the persistence of war in Ukraine, and the rawness of the occupation in the West Bank. Taken together, this category reminded us that the Ibero-American contribution to global photojournalism is no longer marginal: it is central, necessary, and increasingly influential.

OPEN CATEGORIES

The open categories of POY Latam were created as a space to expand the boundaries of photojournalism and explore new visual languages. While the classic categories focus on direct testimony, these seek to recognize the plurality of ways in which stories are told today: from creative manipulation and the reworking of archives to experimentation with multimedia, photo books, and long-term projects.

In their reflections, the judges insisted that what is decisive is not the technique or the format, but the honesty of the gaze. A strong open project is not defined by artifice or spectacle, but by its ability to broaden our understanding of the world, to challenge the viewer, and to offer narratives that could not have been told otherwise. Particularly valued were the coherence between form and content, the ability to sustain a personal voice, and the respect for the dignity of the subjects represented.

From the authorial experiments of Nuestra Mirada to the critical interventions in Resignifying the Archives; from the fidelity of Long-Term Projects to the freshness of New Talents; from the immersive narratives of Multimedia to the material richness of Photo Books, these categories demonstrated that Ibero-American photography is living a moment of great vitality. The judges agreed that this intersection between journalism, art, and memory does not weaken photojournalism: it enriches it, renews it, and projects it into the future.

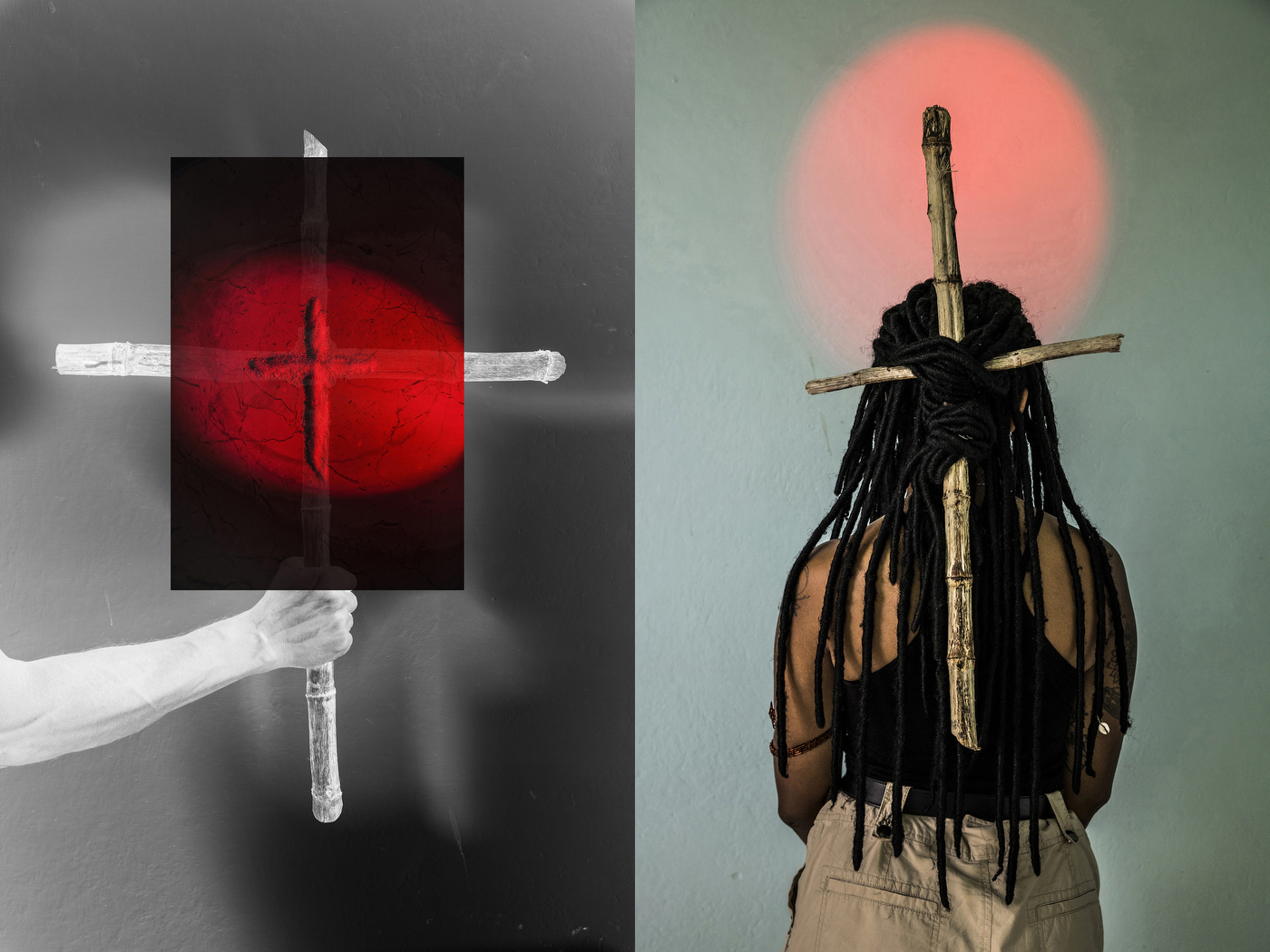

Nuestra Mirada

When it was first introduced in 2011, Nuestra Mirada was a disruptive category: it opened an unprecedented space for works situated on the border between journalism and art, allowing digital manipulation and more subjective explorations. Since then, it has become the most popular category of POY Latam, a true laboratory where photographers dare to cross languages and experiment with new ways of narrating reality.

In this edition, the jury faced the challenge of evaluating very diverse proposals: from digital collages that rewrite historical archives to intimate explorations of identity and gender. The discussion revolved around a central question: how do we distinguish empty artifice from experimentation that brings meaning? The judges stressed that what is decisive is not the technique used, but the honesty of the gaze, the ability of the images to challenge the viewer, and to expand our understanding of the present.

The highlighted projects embodied this fertile intersection between art and journalism: stories that reimagine colonial memory, essays exploring gender violence through self-portraiture, or visual interventions that confront political violence with poetic symbols. The winning work was celebrated for its formal boldness and the coherence of its narrative, showing that subjectivity can also be a path to truth. For the judges, Nuestra Mirada remains an emblematic category because it reflects the way many contemporary photographers move between territories: the documentary and the artistic, the intimate and the social, the real and the imagined.

Long-term Projects

In a world dominated by urgency and immediacy, Long-Term Projects remind us that certain stories can only be understood with patience, consistency, and commitment. The judges emphasized that this category does not reward only the aesthetic quality of the images, but also the ability to accompany vital, territorial, and cultural processes over the years. It is, in essence, an exercise in fidelity: remaining alongside a community, an individual, or a conflict, allowing time to reveal its multiple layers and meanings.

During the deliberations, the difference between a one-off essay and a true long-term project was highlighted. While some works offered a “flyover” of the subject, the strongest projects showed a carefully constructed sequence, where each image contributed to the overall narrative. The judges especially valued those essays in which the photographer managed to transform complexity into clear visual narratives, built with respect and depth, avoiding stereotypes or the easy resource of spectacle.

The selected projects address central issues of our region: migration and displacement, defense of the Amazon, the search for the disappeared, feminist struggles, and the memory of social conflicts. What made them stand out was not only the power of their themes, but the way they were told: with closeness, with personal involvement, and with an ethical awareness of what it means to represent the lives of others. This category reminds us that the long term is not just a measure of time, but a way of seeing: slow, attentive, and committed to the truth of human processes.

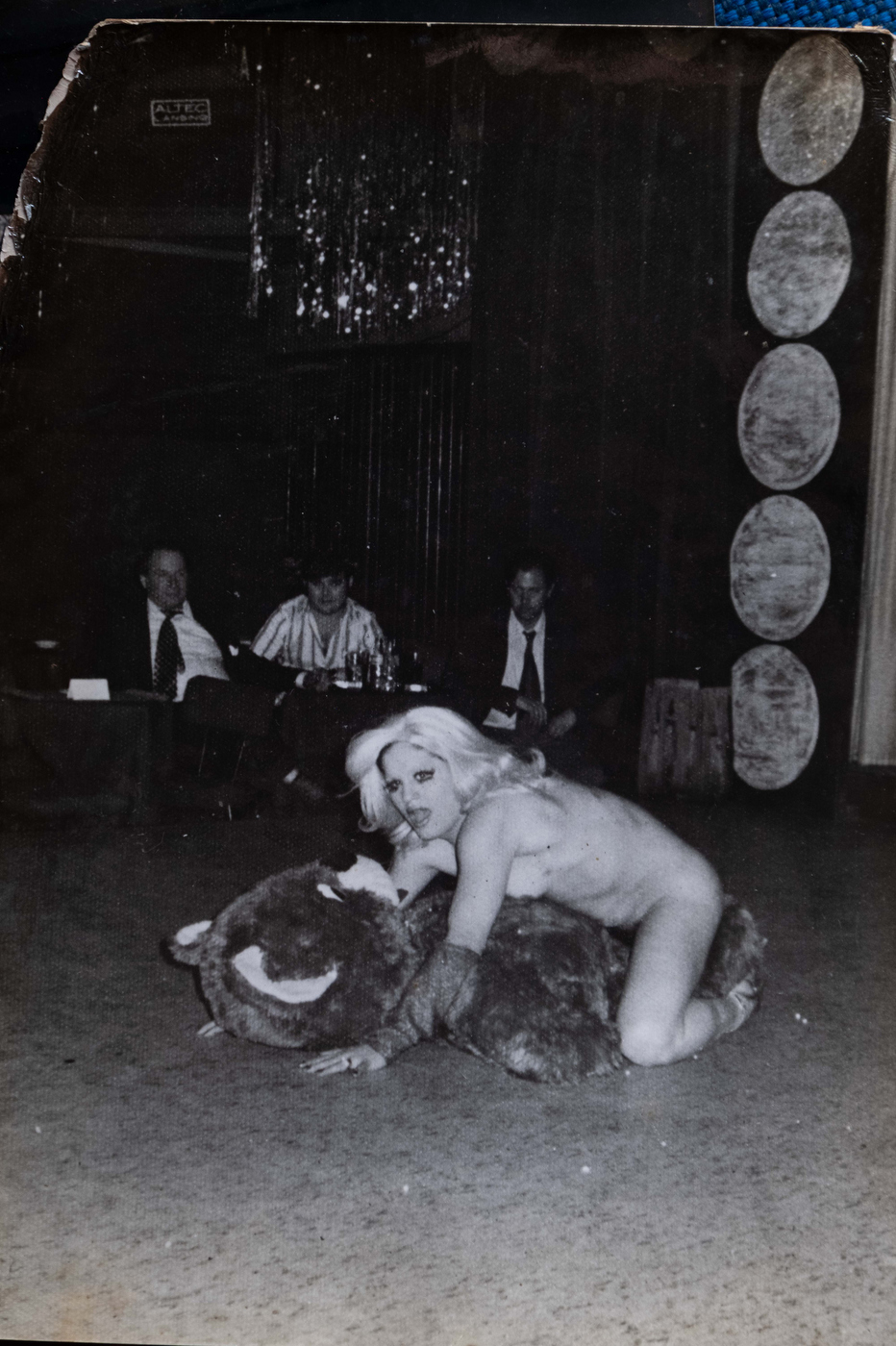

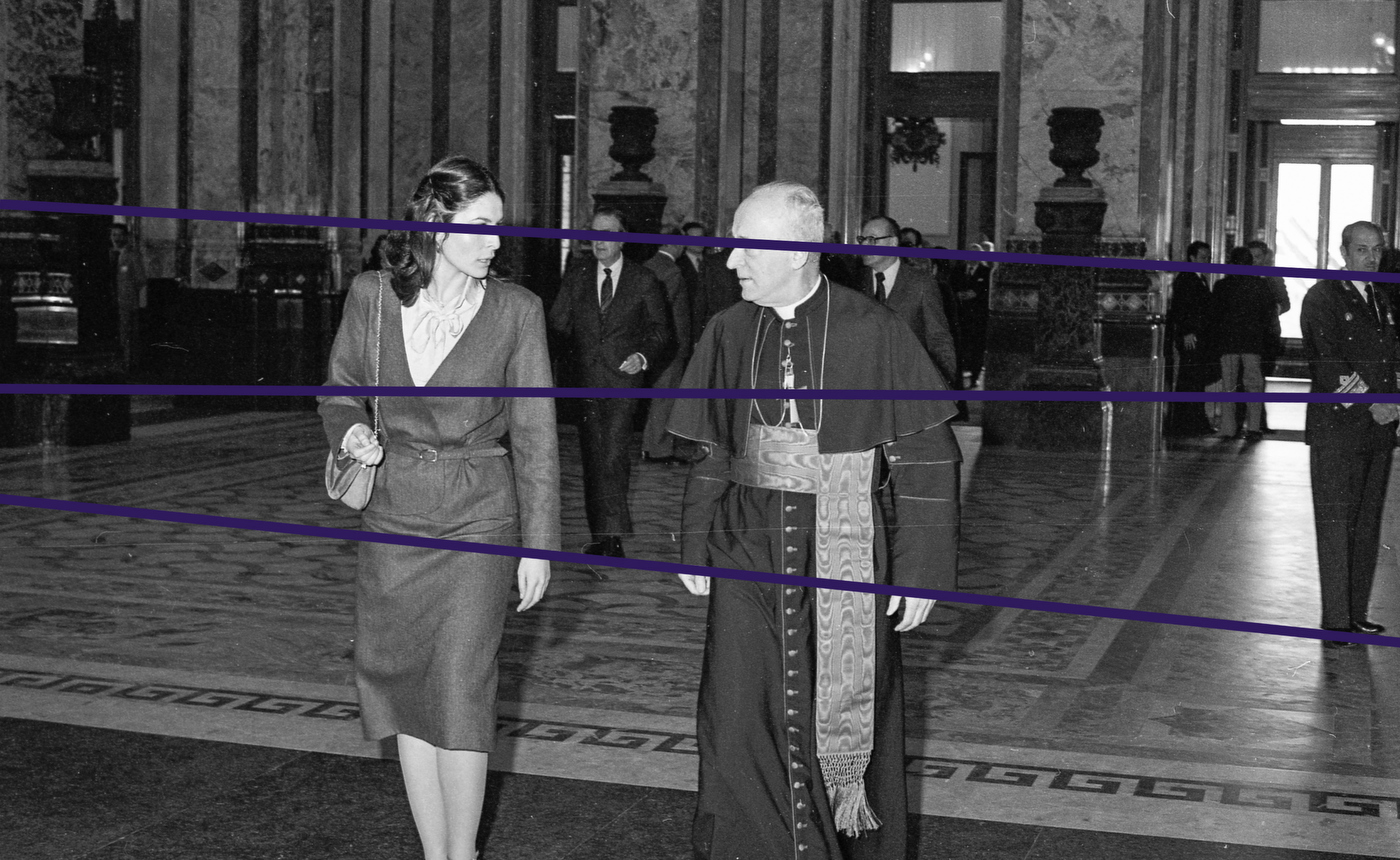

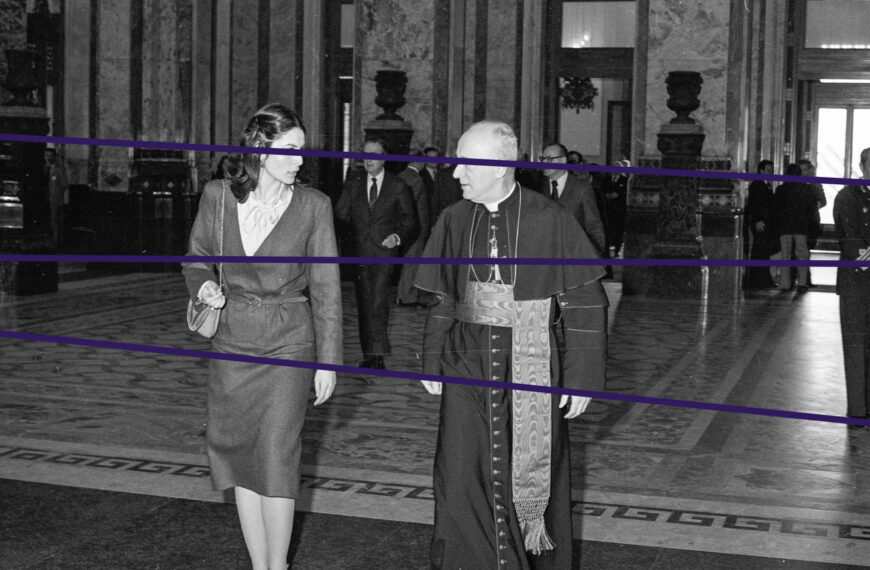

Resignifying the Archives

This category invites us to look back and ask how the past continues to shape the present. Since its creation, Resignifying the Archives has established itself as a space of experimentation and memory: a terrain where the personal intertwines with the political, and where photographers and visual artists question the ways in which archives have constructed—and at times distorted—our history. The judges stressed that it is not only about intervening in old images, but about opening critical dialogues with them, revealing silences, tensions, and possibilities of symbolic repair.

The finalist projects encompassed a wide range of approaches. From the recovery of photographs from Uruguay’s dictatorship that showed the systematic invisibility of women in spaces of power, to the intervention of a family archive to denounce the violence of machismo, alcoholism, and its scars across entire generations. Other works explored religious and sexual memory through monstrous self-portraits built upon family albums; the story of Tania Navarro, a trans woman who survived Francoism and today stands as a symbol of resilience; or the resignification of the trauma of Colombia’s armed conflict through the moss of the páramos, transformed into a metaphor of resistance and memory. Projects addressing intrafamilial sexual abuse also stood out, reframing the domestic archive as a field of denunciation and healing.

The jury recognized El Tetas as the winning project, which, by intervening in a family archive marked by alcoholism and abandonment, succeeded in building a raw and visceral narrative that blends denunciation, memory, and reconciliation. Other works—such as Malignas Influencias, with its monstrous interventions on religious archives; the project on Tania Navarro; and the explorations of trauma and violence in Colombia and Peru—were distinguished as notable. For the judges, this category reaffirms the power of the archive as a field of symbolic dispute: a place where pain is transformed into narrative and where memory becomes a tool of resistance.

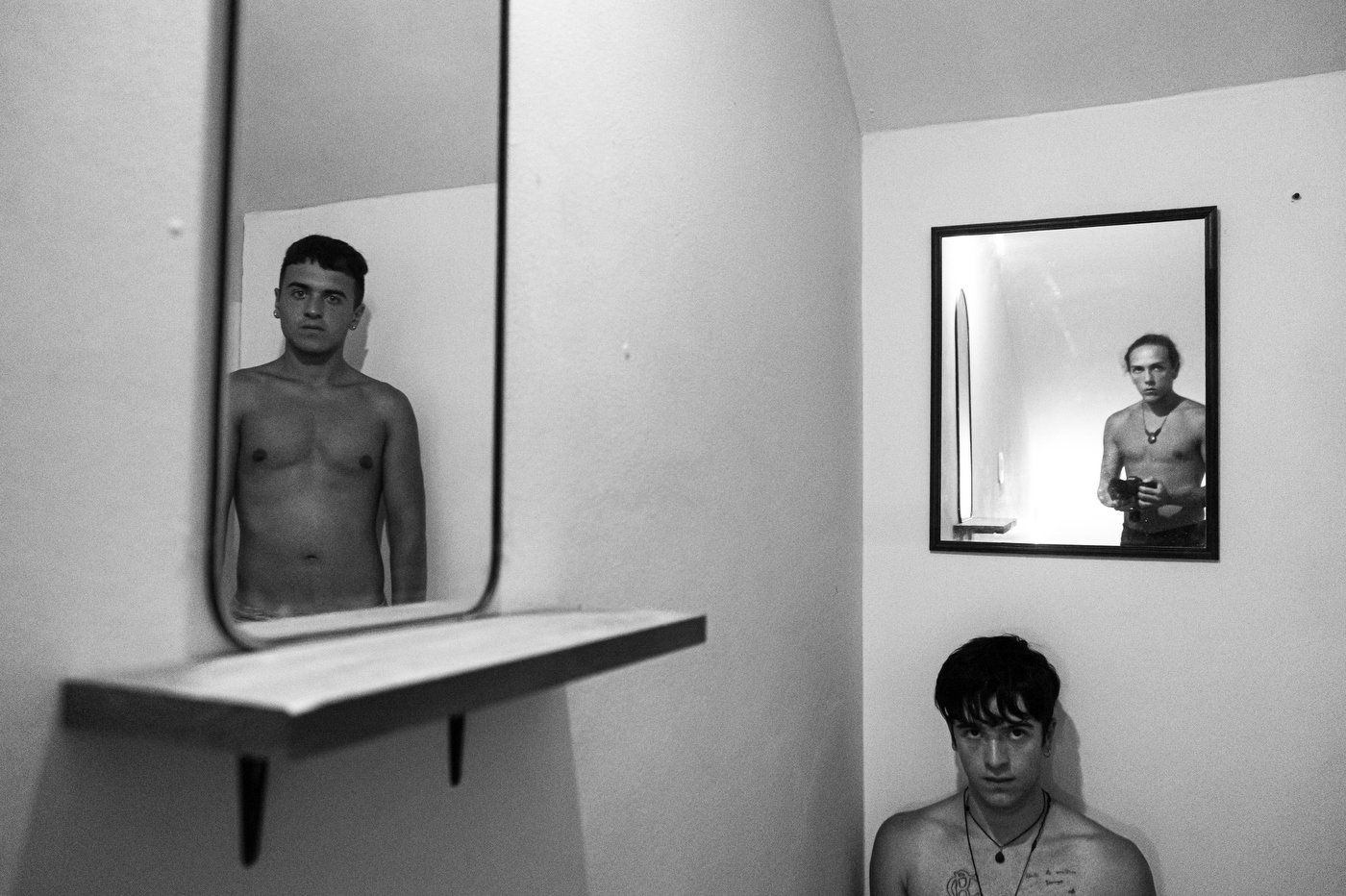

New Talents

The New Talents category seeks to recognize and support photographers with less than five years of experience. It is not about rewarding “immaturity,” but about celebrating the courage of those who dare to experiment, to narrate from the intimate, and to explore languages that expand the boundaries of documentary and artistic photography in Ibero-America. The judges emphasized that what matters here is not formal perfection, but the authenticity of the search, the ability to build a personal voice, and the honesty with which each author approaches their subjects.

The finalist projects revealed the richness and diversity of these emerging perspectives. There were essays narrated in the first person, such as that of a trans woman who portrays herself and her community with poetic strength; works that addressed life under construction and the weight of masculine labor through self-portraits infused with exhaustion and dignity; and intimate explorations of sibling relationships, such as the series on triplets living between tenderness, chaos, and sensuality. There were also projects with a strong symbolic and experimental charge, using collage, performance, or plastic intervention to ask what love, identity, or memory mean in our time.

The winning essay—focused on the lives of three triplet brothers—was celebrated for its sensory power, its physical closeness, and its ability to narrate a unique situation with both rawness and tenderness. Other works were recognized as notable: the series on the trans community and its right to visibility; Cero Plumas, with its daring and poetic collages; self-portraits on identity and memory; and a project exploring women’s prison life through visual metaphor. For the judges, all of them confirm that the region’s new talents not only continue the documentary tradition but also expand it into hybrid territories, where the personal and the collective, the real and the symbolic, intertwine to shape new narratives.

Carolina Hidalgo Vivar Award

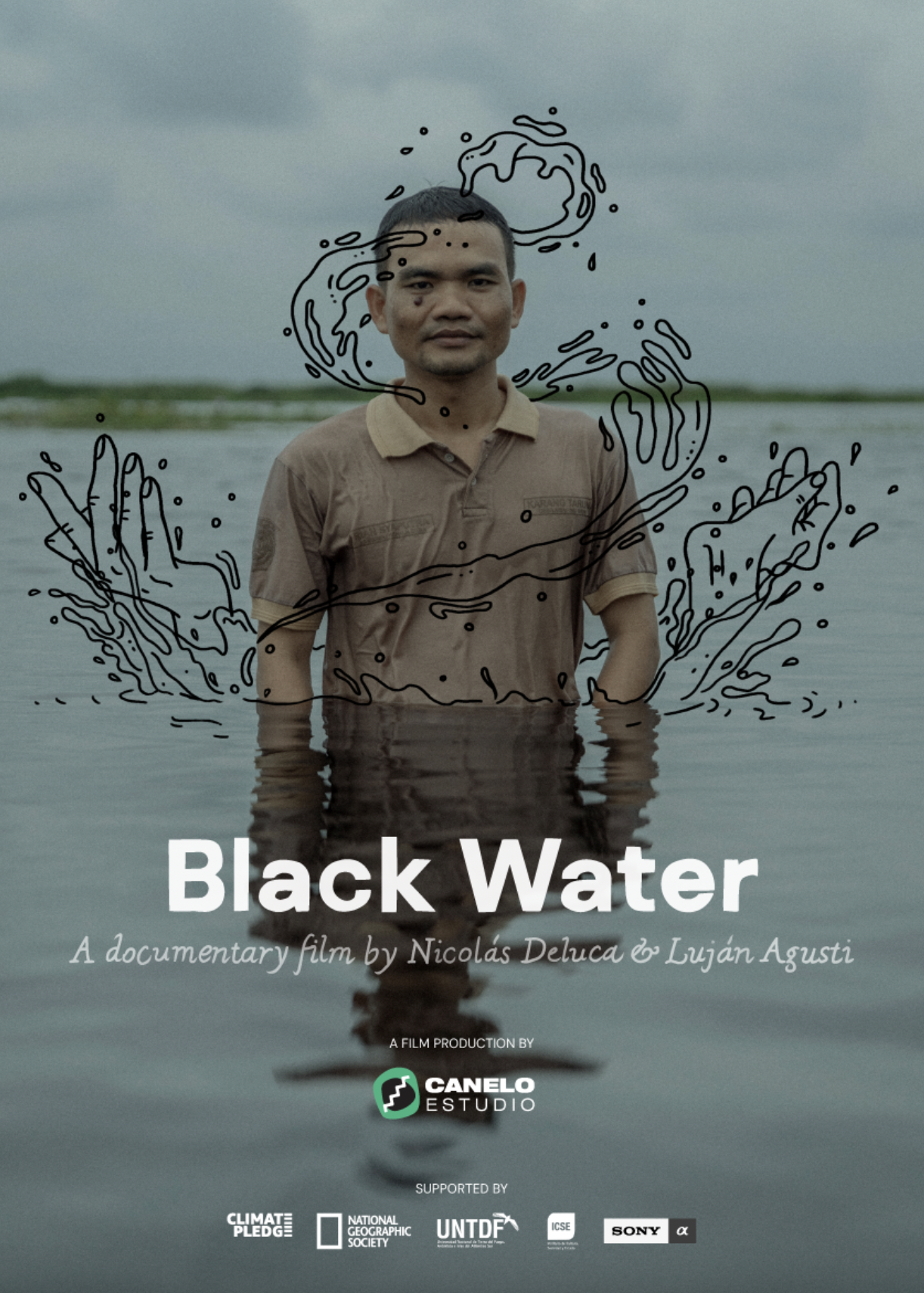

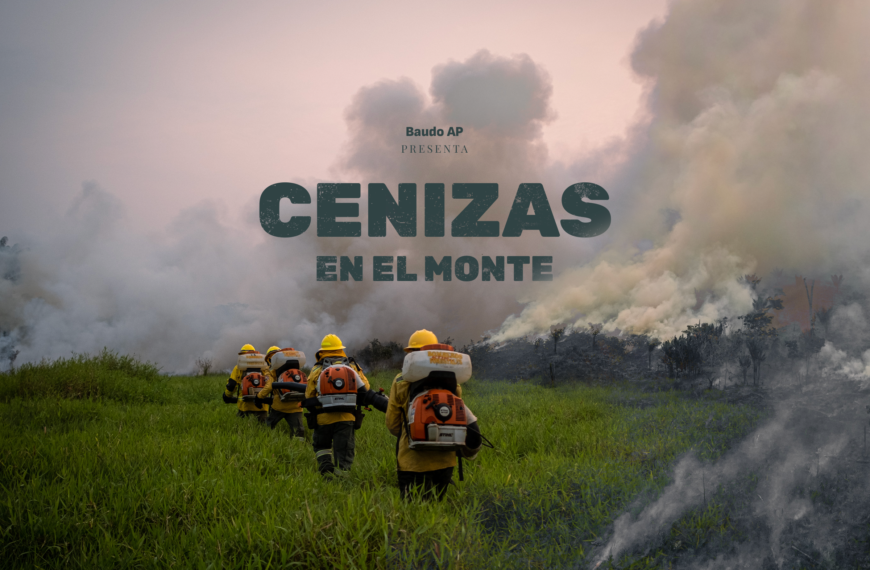

Environment

This award honors the memory of Carolina Hidalgo Vivar, a brilliant and visionary landscape architect, who defended the idea that protecting nature is not only a technical or legal matter, but an act of love, tenderness, and responsibility. Her legacy inspires this category to celebrate those who fight for the land, the water, and life in all its forms, reminding us that the environment is not a peripheral issue but central to our very existence.

In their deliberations, the judges reflected on the risks of falling into overly literal visual language—felled trees, dry rivers, fires—and highlighted the value of fresh, authorial, and poetic perspectives that renew the way we see the ecological crisis. They discussed the importance of projects that not only show consequences but also highlight resistance and alternatives: from women’s brigades fighting wildfires in Argentina, to communities seeking to recover an ancestral color lost in their textiles, to peoples who make pilgrimages to glaciers to keep alive the rituals that maintain balance with nature.

The winning essay, A Dream in Blue, was celebrated for its beauty and for the way it turns the reforestation of a single plant into an act of cultural and environmental resistance. The judges noted that this work opens a horizon of hope in times marked by apocalyptic narratives, reminding us that photography can not only denounce destruction but also illuminate pathways toward a possible future. Other projects—on the defense of cenotes in Mexico, women’s firefighting brigades, and the intimate lives of families resisting in arid territories—were recognized as notable. Taken together, this category reaffirmed that to see the world through Carolina’s eyes is to do so with sensitivity, respect, and commitment to all living beings.

Identity and Gender

The Identity and Gender category has become a central space for reflecting on the struggles, bodies, and narratives that shape women, sexual dissidences, and Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities in Ibero-America. The judges emphasized that here photography is not only testimony, but also a field of experimentation where the personal becomes political and where images engage with family memories, social wounds, and processes of resistance.

Among the most discussed works were those addressing femicide in Mexico and its consequences for children, with projects that, through an aesthetic of tenderness, document girls and adolescents orphaned by the murder of their mothers. The jury also highlighted the power of essays that reconfigure masculinity through performative self-portraits, questioning what it means to “be a man” in a time of ruptures and transformations. Other projects dealt with racial discrimination in Cuba, using Afro hair as a symbol of resistance, or with intimate processes of healing in families marked by machismo, violence, or mental illness.

The jury selected Cuidar ante la ausencia (Caring in the Absence) as the winning project, which portrays the lives of children orphaned by femicide in Mexico. It was praised for its ability to combine denunciation and tenderness, memory and resilience, through a visual language built collaboratively with the families. Other works, such as Pelo Malo (Bad Hair), which confronts racism in Cuba; El acto de ser él (The Act of Being Him), which explores the tensions of masculinity; and intimate essays on family bonds and trans resilience, were recognized as notable. Taken together, this category reaffirms that identity and gender are not marginal issues, but central axes for understanding both the violences and the strengths of our region.

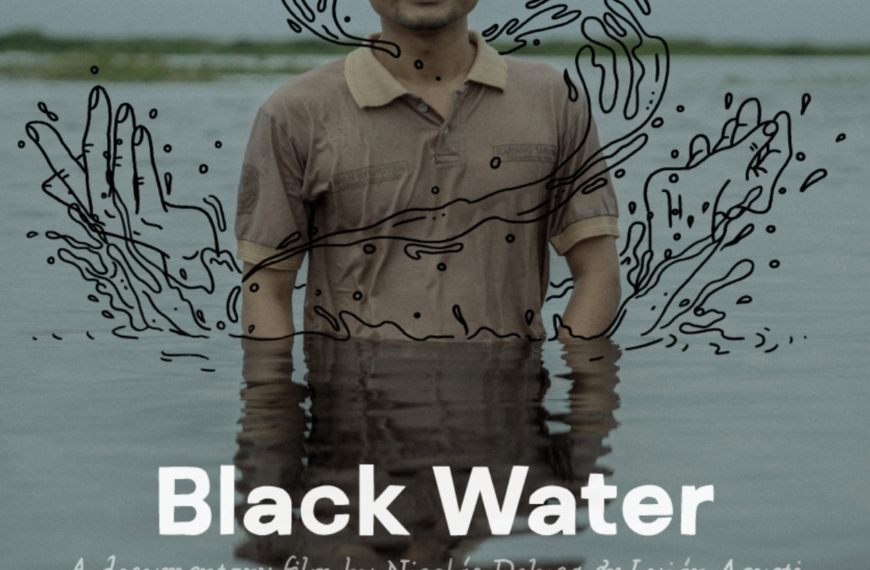

Multimedia

The Multimedia category reflects how visual journalism expands beyond still photography, exploring the possibilities of sound, video, animation, and interactivity to build more complex narratives. The judges emphasized that what matters here is not the technology used, but the way all the elements are integrated to give strength to a story. A good multimedia project must achieve what photography alone cannot: offering immersion, context, and a narrative experience that engages the viewer in new ways.

During deliberations, the originality of projects addressing urgent issues from innovative perspectives was highlighted: portraits of drag communities breaking stereotypes, visual interventions on family archives, works denouncing environmental devastation in the Amazon, or intimate stories mixing performance and photography. The judges discussed with particular interest how some projects managed to strike a balance between the poetic and the informative, avoiding both technological overload and the risk of diluting the message in artifice.

The jury awarded those works that, beyond visual impact, demonstrated narrative coherence and a creative use of digital resources. It was recognized that these proposals expand the boundaries of Ibero-American photojournalism and show how new generations are embracing multiple languages to continue telling essential stories. The Multimedia category reminded us that the strength of a narrative does not lie in its medium, but in its ability to move us, to challenge us, and to expand our understanding of the world.

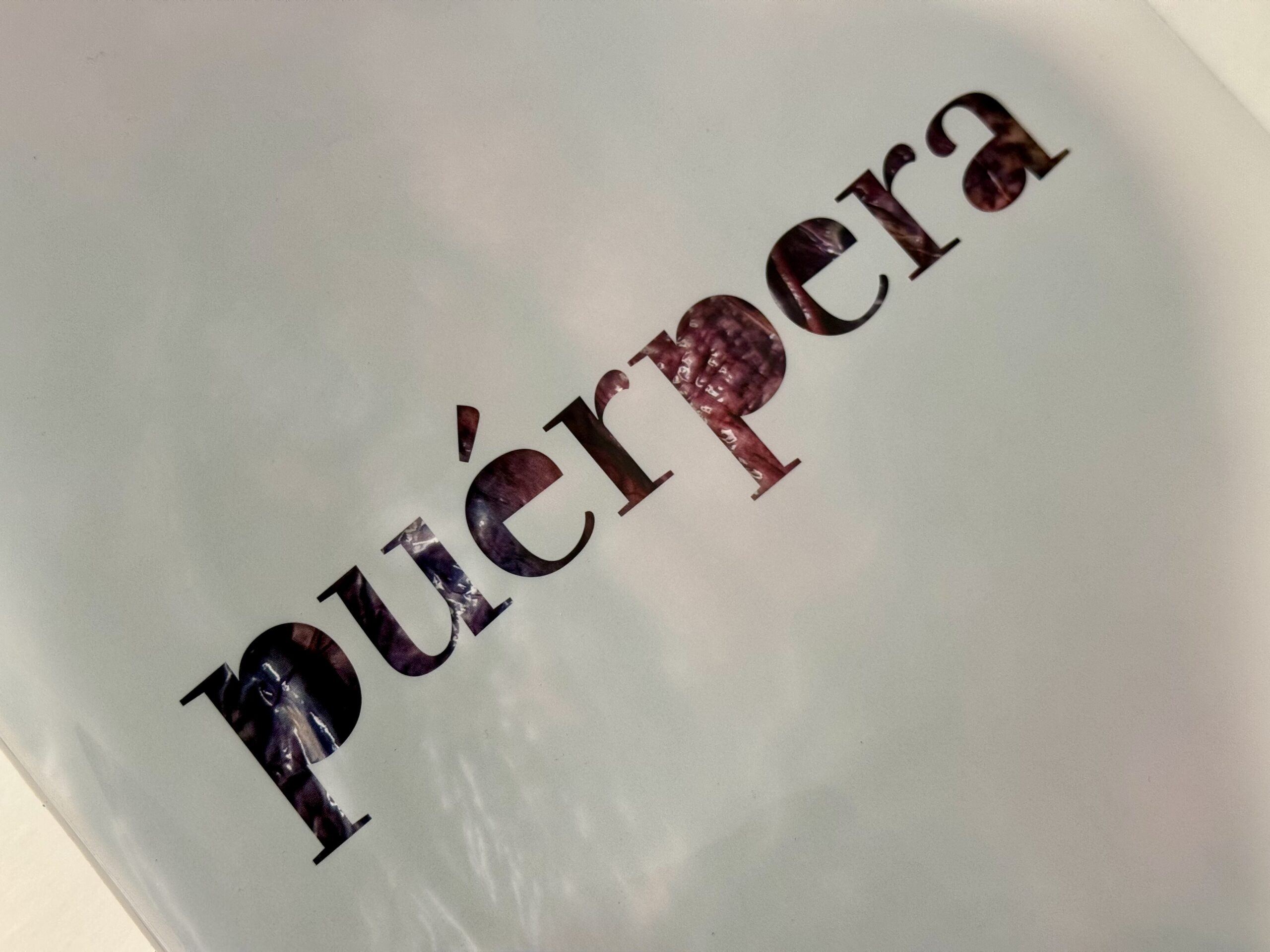

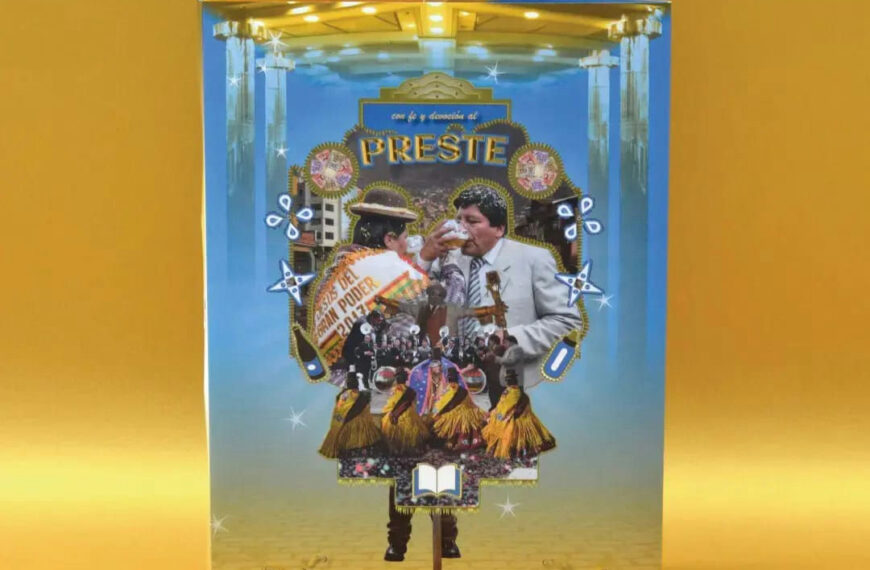

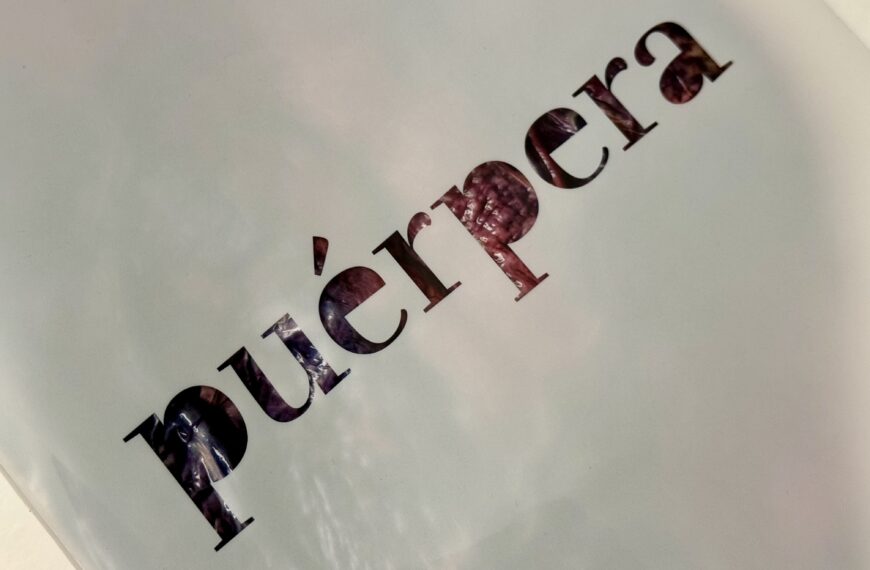

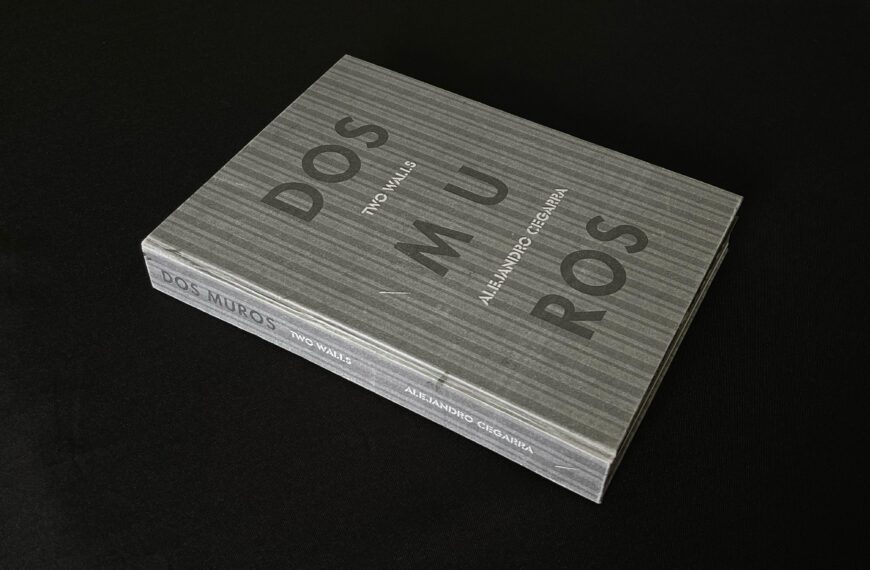

Photo books

The Photo Books category has grown to become one of the most anticipated at POY Latam. The judges highlighted how, in just over a decade, editorial production in the region has not only multiplied but also reached a high level of professionalism. The photo book is no longer a marginal object but a vibrant ecosystem that brings together photographers, editors, and designers, and has established itself as one of the most powerful languages for telling visual stories in Ibero-America.

In deliberations, it was stressed that a great photo book does not depend solely on the quality of the images, but on the coherence between content, design, materiality, and narrative. The judges discussed how some works functioned more like catalogs than as books with a distinct voice, while others achieved a masterful balance between photography, text, and object. They especially valued those projects that, beyond offering strong images, built immersive atmospheres, internal rhythms, and visual metaphors that invite the reader to return to their pages again and again.

The winning book was recognized for its ability to weave together research, memory, and design into a profound and moving narrative, while other works were distinguished for their freshness, formal boldness, or commitment to urgent regional issues. Taken together, this category reaffirmed that the photo book today is one of the richest forms of contemporary photography: a space where the intimate and the collective, experimentation and testimony, poetry and document intersect.